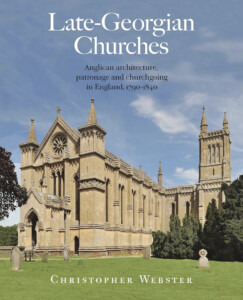

Late-Georgian Churches

Anglican Architecture, Patronage, and Churchgoing in England, 1790-1840

By Christopher Webster

John Hudson Publishing, 320 pages, $115 cloth, $29.95 digital

Since the mid-19th century, when the Cambridge Camden Society, also known as the Ecclesiologists, began to advocate for medieval “pointed” architecture as uniquely appropriate for sacred buildings, the Gothic Revival has held a privileged position as the “correct” style for churches. A side effect of the Ecclesiologists’ very successful advocacy for Gothic has been a certain disregard for the classically styled church buildings dating from the immediately preceding years around 1800, which the Ecclesiologists unfairly disparaged as plain and undistinguished. Christopher Webster’s thoroughly researched and carefully argued book, copiously illustrated with 378 beautiful new photographs by Geoff Brandwood, aims to revise that conventional wisdom.

Webster argues that, at a time when the established church faced challenges both external (the growth of Nonconformism and Catholicism, the Napoleonic wars, alienation from the lower classes) and internal (inefficiencies, mismanagement, and abuses), the building program that produced over 1,500 new churches was an expression of confidence. In an era that prized the importance of reason, the national church wanted to discourage both Nonconformist “enthusiasm” and Roman “superstition”; thus, both in liturgy and architecture, the idea of rational, well-ordered worship guided many decisions.

This is evident, for example, in the floor plans of the buildings. In contrast to both Catholic churches (which placed the central focus on the altar), or Nonconformist Protestant chapels (which centered on the preacher in the pulpit), Anglican churches strove for a harmonious accommodation of both pulpit and altar. Still, the “auditory worship” of spoken Morning and Evening Prayer was the top priority in shaping these buildings (which the Ecclesiologists later dismissed as “preaching boxes” or “sermon houses”), and Communion was less frequent, which meant that the pulpit was usually more prominent than the altar. Singers and musicians were placed in galleries well away from the chancel (to emphasize their secular status), and the distinctive three-decker pulpit placed the clerk at the bottom, the middle level for reading the service and prayers, and the top level for preaching the sermon, so it could be clearly heard throughout the space.

As regards the question of style, the Classical predominated until the end of the 18th century because it was seen as rational and harmonious in form. By the early 19th century, however, even before the rise of the Ecclesiologists, the Gothic had begun to rise in popularity because of its association with English tradition and the historical continuity of the church (as against French radicalism). For readers familiar with the eventual triumph of the Gothic, Webster’s presentation of important Classical achievements such as St. Chad’s Church, Shrewsbury (George Steuart, 1790-92), or St. Peter’s, Walworth (John Soane, 1823-25), will be novel and enlightening. In its richness of detail, this book can also serve as a guide to social and economic aspects of the Church of England during the period in question. Thoroughly practical questions — who pays for a new building, how the financing will be arranged, where it will be located, and how big it needs to be — shed light on the worldly side of spiritual matters. Pew rents, for example, were seen as regrettable but unavoidable, given the need for funds. In booming industrial areas, congregations overflowed the space available in existing churches, but the working class could not pay for expensive new buildings. Showing how countless, now-obscure, local clergy and lay leaders responded to such challenges to create works of real beauty, Webster’s book splendidly recovers an unfairly maligned period of architectural history, and introduces readers to a set of monuments worth appreciating in their own right.