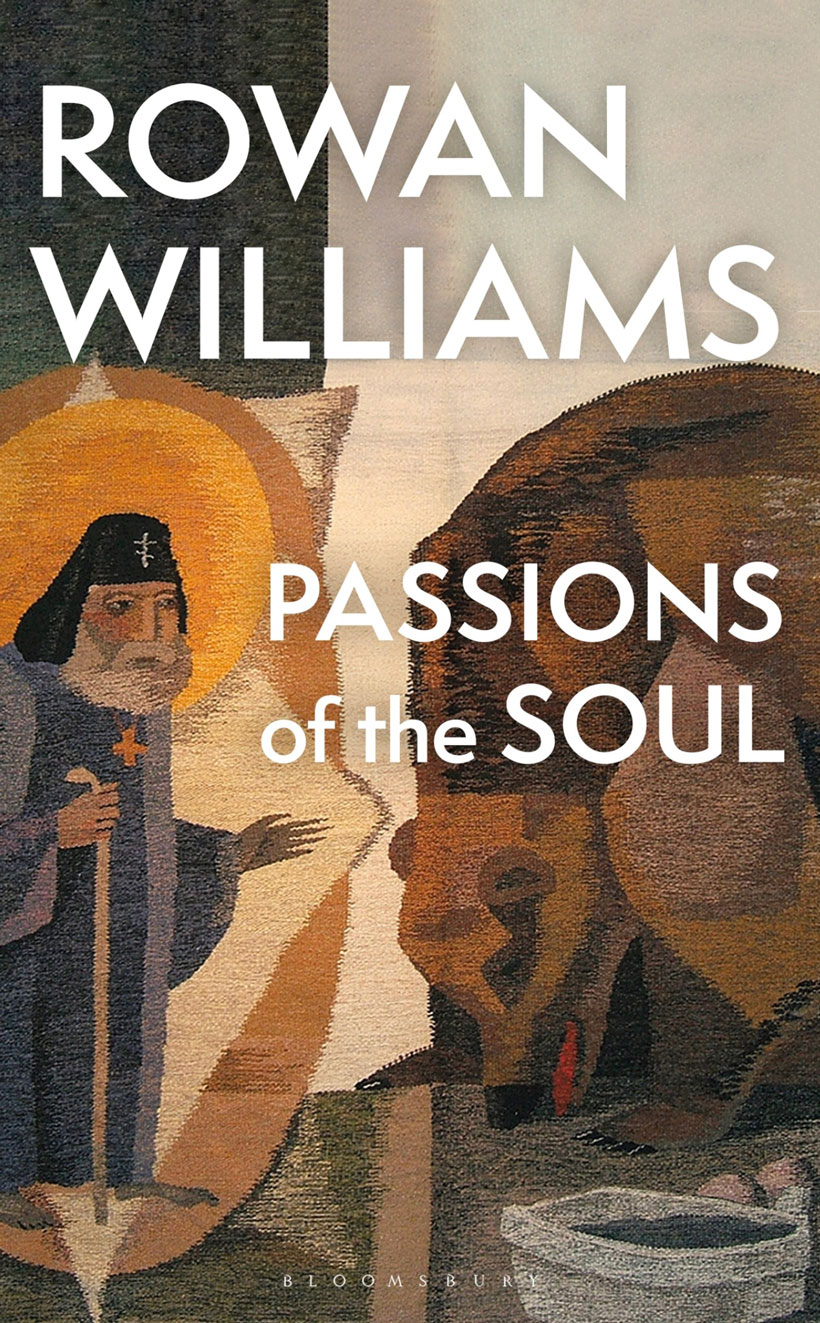

Passions of the Soul

By Rowan Williams

Bloomsbury Continuum, 121 + xxxiv pages, $15

At the heart of this slender volume is a series of retreat addresses Rowan Williams first presented to the Anglican Benedictines of Holy Cross Convent in Leicestershire, which he later reworked and to which he added a couple of related essays. As it happened, I brought Passions of the Soul with me for a recent retreat, where I experienced through a slow, meditative reading of the text Williams’s unfailing pastoral insight. It is a gem. Like some of Williams’s other short books based on retreat addresses — his two sets of meditations on select icons of Christ and of Mary come to mind — Passions of the Soul merits multiple readings to savor the superb wordcraft and absorb the wisdom of its pages.

At the heart of this slender volume is a series of retreat addresses Rowan Williams first presented to the Anglican Benedictines of Holy Cross Convent in Leicestershire, which he later reworked and to which he added a couple of related essays. As it happened, I brought Passions of the Soul with me for a recent retreat, where I experienced through a slow, meditative reading of the text Williams’s unfailing pastoral insight. It is a gem. Like some of Williams’s other short books based on retreat addresses — his two sets of meditations on select icons of Christ and of Mary come to mind — Passions of the Soul merits multiple readings to savor the superb wordcraft and absorb the wisdom of its pages.

The brief foreword and lengthy introduction orient the reader to Williams’s topic: the teaching of early Eastern monastics on the principal interior obstacles to spiritual growth and strategies for overcoming them. He centers his exposition on texts written in 450-750, but also draws on earlier material, especially from Evagrius of Pontus (d. 399), as well as later works in that treasury of Eastern monastic writing, the Philokalia. The introduction frames the rest of the teaching that is to come, and I focus my remarks on this early, informative material. Book I then delves into the eight “passions” as interpreted in the tradition; Williams also juxtaposes each of the eight Matthean Beatitudes as counter-remedies to them. The two essays of Book II survey the goal of Christian spirituality — or the challenge “To Stand Where Christ Stands” — from Paul through patristic writers to Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross. These chapters elucidate foundational questions from various angles, while indicating an essential unity in the spiritual quest across the centuries.

The passions under consideration are symptoms of a fundamental loss of freedom in the human soul. While we might think of passion, positively or negatively, as intense desire, the “fire in the belly” (Williams wryly observes that nowadays no CV is complete without a disclosure of one’s “passion” for the work), these uses of the word are secondary to the monastic authors. Passion is employed in their ascetical grammar in its root sense to indicate something we do not so much choose as undergo, even suffer.

Western Christians might recognize it as the condition stemming from original sin — parsed by Williams as the “spiritual handicaps we haven’t chosen but are stuck with.” Chief among these is the mental skew of “illusion,” which prevents us from seeing things as they are, in their natural simplicity, with clarity of vision. Instead, we tend to approach the world (including others) with the unstated questions, “What’s in it for me? How will this affect me or mine?” A self-centered perspective is seriously off-center, but we can’t seem to help it.

Small wonder early theologians referred to baptism as an “illumination”: the grace of seeing with the lights on; seeing, by small increments, the truth. But maturing into the baptismal life, of healing our disoriented and fractured selves, requires at least a lifetime of consistent ascetical effort. Our deep hope is grounded in the grace of Jesus Christ, who by his incarnation, death, and resurrection took our evil upon himself and transformed it. The Spirit opens a way into freedom, a defining quality of resurrection life. We are further helped by our innate longing for God, given in creation, what Williams calls “a kind of magnetic turning towards the real.”

Meanwhile, we need practical help to see straight, and here is where the early tradition comes to our aid. Williams insists, rightly, that these centuries knew no distinction between “theology” and what we would call “spirituality”; indeed, “Christian doctrine took its distinctive shape only through reflection on the distinctiveness of how Christian women and men actually prayed.” The guidance of the early monastics was shaped by their personal and corporate experience of struggle and prayer, their keen observations of the workings of their hearts, and the interventions of divine grace usually enacted in quite ordinary circumstances.

The passions are those framed by Evagrius of Pontus as the “Eight Thoughts,” which in turn passed into the Western tradition via John Cassian as the Seven Deadly Sins. This was an unfortunate recasting of Evagrius’s insightful diagnosis of our spiritual maladies, for what is at issue are not so much discrete acts of sin (although they can morph into sin) as thoughts, notions. Evagrius calls them logismoi. In his opening chapter, “Mapping the Passions of the Soul,” Williams shrewdly describes them as “corrupt chains of thought”: not mere “strings of mental ramblings but chains that bind us.” These logismoi can make us their prisoner, but it is possible to break these destructive bonds before they take over. Watchfulness over our thoughts from the very start is key here. Once we notice a vicious pattern beginning to lodge itself in our minds, we face it without undue anxiety and hand it over to God, casting ourselves upon divine mercy for help. Finally, we simply turn our attention to whatever task may be at hand and get on with it. No fuss.

Attaining the condition called apatheia is the object of these practices, but we must not confuse it with its entomological English relative, “apathy.” (Indeed, apathy could be traced to indifference or acedia, one of the deadly thoughts — what Williams characterizes as a cynical, perhaps coping, “whatever” attitude.) By contrast, apatheia is an “anticipation of the resurrection” (xiv), a state of inner freedom from enslaving, disordered, compulsive passion. Only apatheia makes authentic love possible, since it is free from our usual set of demands, whether spoken or not. “Apatheia has a daughter named agapé,” wrote Evagrius.

The aim here is to get beyond purely reactive responses to whatever life serves up. Humans have evolved a whole set of instinctive responses to situations that may please or threaten, instincts that have helped us survive and cope, and thus serve up to a point. But they have their limits. As Williams notes,

We have to negotiate our way by means of these instincts, yet they can get in the way of our full humanity if we don’t think through how they work. … For the Eastern Christian writers, “passion” is the whole realm of instinct, reaction, coping mechanisms, and this is the level at which complications arise. We cannot live without these things if we are to be human at all; yet unless we understand and in some degree transfigure them, we are trapped in something less than human. (xxii-xxiii)

As Williams, following the ancient writers, teases apart each of the Eight Thoughts along with its corresponding ameliorative Beatitude, we see the integrative theology of the Church’s first thousand years working to support praxis. The labor of habitual wakefulness does not take place in the echo chamber of one’s private thoughts, however. Its context is the faith and sacramental life of the community, and “it develops as we live a life involved with others, as we respond to situations and cope with a fluid and changing environment. … God has so shaped the world that we grow into our deepest freedom in a world of constraints and challenges.”

The teaching of these ancient guides is fundamentally hopeful. We don’t have to be trapped in self-defeating reactions that shrink our humanity, destroying the exchange of love with God and others for which we were made and for which we are destined in Christ. But we need education in the often subtle ways of the Spirit to get our bearings, sharpen our discernment of what’s really going on, and thus sustain a faithful response. Passions of the Soul offers such a needful mentorship.