From The Living Church, April 16, 1898

News and Notes

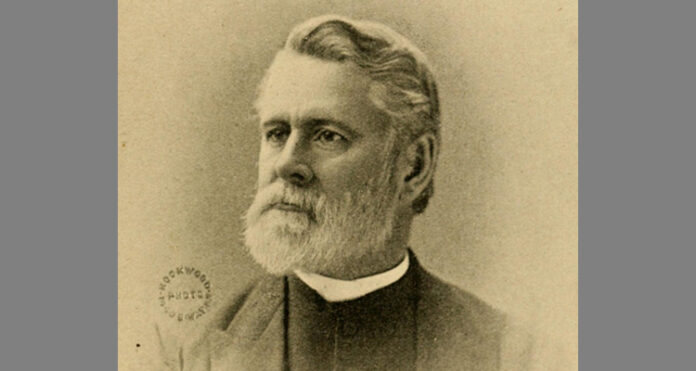

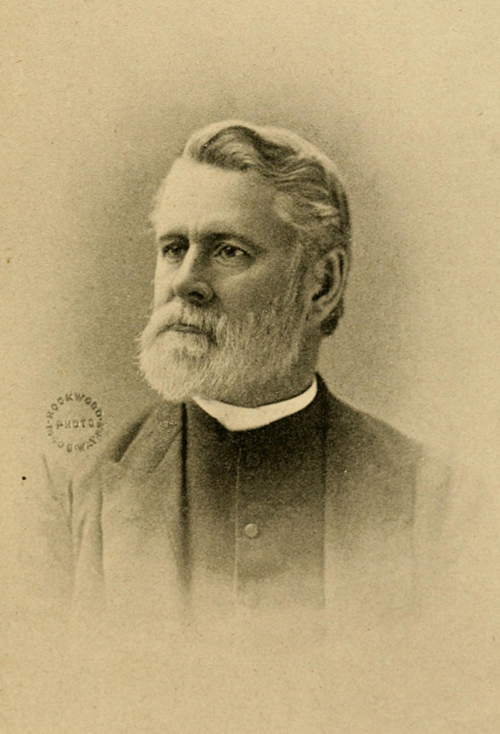

It is announced that Dr. Chas. A. Briggs, Edward Robinson Professor of Biblical Theology in the Union Theological Seminary, has just received the rite of Confirmation by Bishop [Henry Codman] Potter [of New York]. Dr. Briggs, who is under ministerial suspension for alleged heretical teaching, by act of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian denomination, has presented a resignation to the New York Presbytery of all relations with that body, and will immediately apply for Holy Orders. It is not stated that he contemplates leaving the professorship.in the Union Seminary, which claims to be free of control of the Presbyterian authorities.

His daughter has been for some time a deaconess of the Church, having graduated from the Deaconess School of Grace Church, New York City, and Prof. Briggs himself has been attending the worship of the Church. His reception has caused a large amount of comment from the local press, and wide interest in religious circles.

The Case of Dr. Briggs

By Charles A. Leffingwell, Editor

It is announced that the Rev. Charles A. Briggs, D. D., whose case has excited so much dissension in the Presbyterian Church during the last few years, was recently confirmed by Bishop Potter, of New York, and has applied to become a candidate for Holy Orders. Dr. Briggs was tried in 1892 before the Presbytery of New York for erroneous teaching on the subject of authority in religious belief, and with regard to the truth and inspiration of the Old Testament. On this occasion Dr. Briggs was acquitted, but the case being appealed to the General Assembly, the decision of the Presbytery was reversed, and being found guilty of the charges made and of violation of his ordination vows, he was suspended from the office of minister. He continued, however, to occupy the chair of Biblical Theology in the Union Theological Seminary, which, though Presbyterian, is not under the control of the General Assembly.

A question for the seminary is raised by this new departure of Dr. Briggs. It appears that the charter requires that members of the faculty shall be members of the Presbyterian Church. It is doubtful, therefore, whether Dr. Briggs can remain in his present position. Even if he could legally do so, it would be an extraordinary anomaly for a Churchman to be engaged in the work of training young men for the Presbyterian ministry, and this becomes still more extraordinary if he should be admitted to Holy Orders under a vow to “drive away all erroneous and strange doctrines.” It is impossible that any such state of things should be contemplated, or that any bishop would ordain a man to the priesthood under such circumstances. No doubt the question will soon be solved by the voluntary resignation of Dr. Briggs of his position in a Presbyterian seminary.

We cannot, in any case, pretend to feel any particular gratification over the accession of Dr. Briggs to the Church’s fold, unless it has been attended with concessions on his part, of which there has been no indication. Formerly when Presbyterian ministers of eminence came to the Episcopal Church, it was because the doctrine and polity of the Church had won their allegiance. It was a matter of profound consideration and anxious thought. Such men acted under a deep sense of responsibility, and their conversion meant the rooting out of old convictions and the substitution of new ones of a strong and positive character. Such accessions were of unquestionable value to the Church and to the cause of supernatural religion.

But of late years it is to be feared that there is a tendency to seek orders in the Church on very different grounds. It has been recommended as the “roomiest Church in Christendom,” and it has been assumed that it is a proper refuge for men who wish to be untrammeled by any definite Faith. This class of men are generally in rebellion against the most orthodox and conservative tenets of the denomination with which they have hitherto been connected. They seek the Church, not on the conviction, but for lack of conviction.

It is very true that many of the Protestants have in their confessions elevated dogmas which have never been so held in the Catholic Church. Some of these may be held as matters of opinion among us, but they cannot be bound upon the conscience.

In this way the Church possesses a liberty which such denominations do not enjoy, and to that extent we are less trammeled than they. But no one can examine the Prayer Book and its teachings, the Creeds and Articles, the Catechism and the Sacramental offices, together with the Ordinal, without discovering that, there is a large body of positive teaching which is binding upon Churchmen.

Formerly this was well understood, and conscientious men felt, that in connecting themselves with us, they were committing themselves to this teaching. It was hardly needful to provide safeguards to meet the case of men who undertook to exercise the work of the sacred ministry while they played fast and loose with the doctrine they were appointed to teach. If men did not believe the teachings of the Church, they did not seek her ministry merely to escape from the trammels of their own denominations; if, being already in the ministry, they ceased to have faith in the Church, they usually had the grace to retire of their own accord. The necessity of trials on the ground of doctrine was hardly felt, and the machinery of ecclesiastical courts was never properly perfected.

But with the new and lax theories about subscription, it has resulted that men may sign or pledge themselves to any formula of belief, however positive and exact, with some utterly novel interpretation of their own, denuding it of all meaning, or else with the idea that such pledges are mere forms and have no binding obligation. It is doubtless under the influence of such ideas, with the added knowledge that we have no really adequate means of bringing discipline to bear upon erratic and faithless teachers that the Episcopal Church is so often alluded to as the “roomiest Church.”

But with the new and lax theories about subscription, it has resulted that men may sign or pledge themselves to any formula of belief, however positive and exact, with some utterly novel interpretation of their own, denuding it of all meaning, or else with the idea that such pledges are mere forms and have no binding obligation. It is doubtless under the influence of such ideas, with the added knowledge that we have no really adequate means of bringing discipline to bear upon erratic and faithless teachers that the Episcopal Church is so often alluded to as the “roomiest Church.”

The Confirmation of Dr. Briggs has been the occasion of these remarks, though they may not necessarily apply to him in detail. We are too ignorant of the circumstances of his conversion to be justified in classing him with such persons as we have just described. It is true that his views of Holy Scripture, as indicated in various publications, have been such as to cause much anxiety to believers in revealed religion.

At the same time, he is not by any means a clear writer. and may have laid himself open to misconstruction. He appears to have energetically repudiated some of the charges on which he was tried. We shall endeavor to hope for the best, especially since we recall the fact that he cannot be admitted even to the diaconate without signing the following very explicit statement: “I do believe the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be the Word of God, and to contain all things necessary to salvation; and I do solemnly engage to conform to the doctrines and worship of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States.”

Old Testament scholar Charles A. Briggs (1841-1913) was among the first influential proponents of “higher criticism” of the Bible in America. Having studied with pioneers of the movement in Berlin, he used his 1891 inaugural lecture at Union Theological to describe the Old Testament as riddled with errors and to attack the doctrine of Scriptural inerrancy as “a ghost of modern evangelicalism to frighten children.” The Presbyterian Church’s General Assembly responded by vetoing Briggs’ appointment at Union by a margin of 440-60. In response, Union’s faculty voted in 1892 to break its affiliation with the Presbyterian Church, thus becoming the first major American seminary independent of denominational oversight. The General Assembly went on, in 1893, to convict Briggs of heresy and to expel him from the ordained ministry.

The Living Church’s report that Briggs intended to “immediately apply for Holy Orders” were well founded. Less than two months after being confirmed, he was ordained to the diaconate by Bishop Potter, and to the priesthood a year later. He remained a priest of the Episcopal Church and professor at Union Theological Seminary until his death.

The Briggs Case is widely seen as a forerunner of the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy that would sweep across most American Protestant churches in the first half of the 20th century, creating divisions between mainline and evangelical denominations that still persist.