Cornerstones

By Simon Cotton

It’s the tower that does it. Your first sight of Ludlow from afar is drawn to the great middle 15th-century central tower of the church. The gateway to the Western Marches, Ludlow was an important frontier town, whose castle was built around the end of the 11th century to ensure the security of the area by the Lacys, the Marcher Lords mandated by William the Conqueror to secure the border against the unconquered Welsh. It was the administrative capital of Wales in the 16th and 17th centuries. Arthur, Prince of Wales and heir to King Henry VII who had lately married Katharine of Aragon, died here of the “sweating sickness” in 1502, which meant that his younger brother, Henry, succeeded him, becoming king and marrying Katharine. How different might history have been if Arthur had recovered?

Ludlow remains an unspoiled town. The church is surrounded by so much later infilling that you are not aware of its size until you push the door open and enter the vast aisled nave. Before that, though, you have to traverse the rare early 14th-century hexagonal porch — the only others are at Chipping Norton and St. Mary Redcliffe, Bristol. Although there are parts of earlier building from the 12th century onward, what you see in the church today is largely from a middle 15th-century rebuild — and what a rebuild.

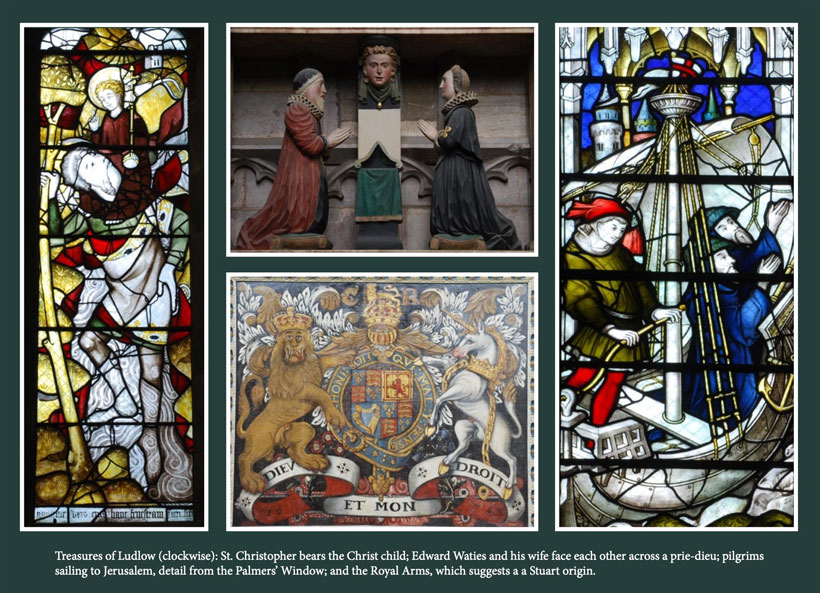

The chapels at the ends of the aisles contain much medieval glass, like a restored Jesse Tree in the south chapel, but this is outdone by the north chapel, where you find the legend of Edward the Confessor and his ring in the “Palmers’ Window.” The story was that King Edward gave a gold ring to a beggar, and sometime later two pilgrims to the Holy Land (palmers) met a man who revealed himself to be the Apostle John, who handed back the ring, instructing them to return it to the king and tell him that he would be in Paradise within six months.

The chapels at the ends of the aisles contain much medieval glass, like a restored Jesse Tree in the south chapel, but this is outdone by the north chapel, where you find the legend of Edward the Confessor and his ring in the “Palmers’ Window.” The story was that King Edward gave a gold ring to a beggar, and sometime later two pilgrims to the Holy Land (palmers) met a man who revealed himself to be the Apostle John, who handed back the ring, instructing them to return it to the king and tell him that he would be in Paradise within six months.

This window is topped by a fine carved medieval canopy of honor. Other windows to notice in this aisle includes Saint Christopher bearing the Christ Child and the Twelve Apostles at the Council of Jerusalem, while one should also look for the small kneeling figure of John Parys and his wife. Parys, a wealthy draper, was warden of the Palmers’ Guild, and died in 1449. There is a fine set of Royal Arms, whose Dieu et Mon Droit motto suggests a Stuart origin, confirmed by the initials CR and the date 1674. The 20th century enters the picture with the banner of the patron, Saint Laurence, by Ninian Comper (1923).

The rebuild of the chancel was completed by 1450 — don’t miss the stalls and misericords, whose subjects include an owl, a dragon-like wyvern, a hart, and a king, as well as some fine post-Reformation monuments, like that to Edward Waties and his wife, who face each other across a prie-dieu (1635). Also spot a putto from the Salway monument.

Here also there is excellent medieval glass. A south window features six of the Ten Commandments, while above the reconstructed reredos is the great East Window. Most of it is taken up with the Passion of the patron saint; above it — at the apex the Holy Trinity, below are the Virgin and Child; St. John the Baptist with the Agnus Dei; St. Anne teaching the Virgin to read; Bishop Spufford of Hereford (1422-48); a king; and St. Laurence.

Returning to the crossing, look up at the tower, building c. 1450-71 with contribution from the guilds — carpenters, smiths, dyers, tailors, cordwainers, butchers, bakers (but not candlestick makers). The great poet A.E. Housman (1859-1936) — who is buried here — celebrated the great tower in verse:

Leave your home behind, lad,

And reach your friends your hand,

And go, and luck go with you

While Ludlow tower shall stand.

Simon Cotton is honorary senior lecturer in chemistry at the University of Birmingham in the U.K. and a former churchwarden of St. Giles, Norwich, and St. Jude, Peterborough. He is a member of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham.